In the hyper-thermic lateritic zones of Birbhum, surface watering is mathematically incapable of maintaining soil moisture. When ambient air temperatures reach 45°C, surface evaporation rates exceed infiltration rates. Water poured onto bare laterite soil does not hydrate it. It seals it by crust formation. At Terragaon Farms, we found that moisture retention depends not on water volume but on breaking the capillary wick effect. By combining a living insulation layer with vertical carbon sinks, we shifted from “watering plants” to “charging the soil battery,” extending crop survival during dry spells from three days to eleven days without intervention.

Why Irrigation Alone Fails in Birbhum

Lateritic soil functions like a heat-driven pump. Water moves upward through capillary action and evaporates rapidly at the surface, leaving salts behind. This creates a crust that blocks further infiltration.

In this system, adding more water increases evaporation losses. The soil dries faster, not slower. Irrigation without insulation accelerates soil death.

The mistake is assuming soil behaves like a container.

In Birbhum, soil behaves like a wick.

The Wick and the Oven Effect

Two destructive forces operate simultaneously.

Bare soil acts as a wick. Solar radiation pulls moisture upward and out. Plastic mulch acts as an oven. It traps heat, cooking soil biology even while conserving water.

Both approaches fail because they ignore biology.

Forest floors are never bare and never hot. That is not coincidence. It is physics plus life.

Root Depth and the Boiling Zone

Frequent light irrigation trains roots to stay in the top four inches of soil. In May, this layer reaches temperatures of 55–60°C. Roots in this zone are effectively boiled.

We shifted to hydraulic lift systems using deep-rooted perennials. Plants like pigeon pea and vetiver pull moisture from deeper layers at night and release it into the topsoil through root exudation, benefiting shallow-rooted vegetables.

Water movement is biological before it is mechanical.

Data Protocol: Heat Dome Trial (May 2024)

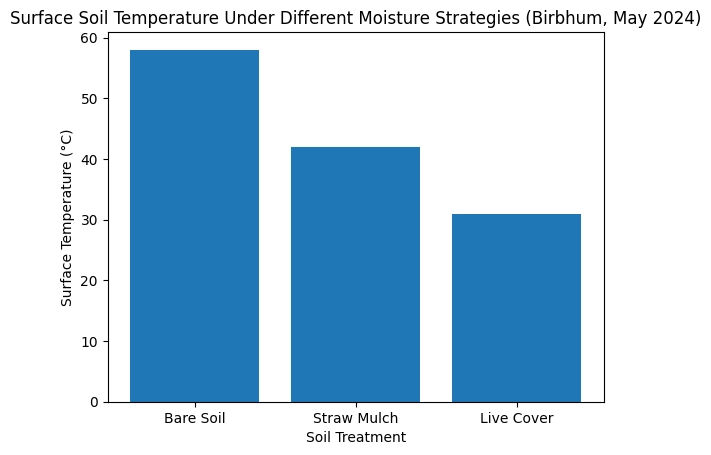

During the May 2024 heatwave, we ran a controlled comparison on three adjacent 100 square foot brinjal plots. Irrigation was stopped for seven days.

| Plot Type | Surface Temp at 2 PM | Soil Moisture Day 7 | Plant Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bare Soil | 58°C | 4% | 100% mortality |

| Straw Mulch (4 inch) | 42°C | 12% | 60% wilting |

| Live Cover (Sweet Potato) | 31°C | 28% | No wilting |

The live cover maintained soil temperatures 27°C cooler than bare ground. Straw mulch cooled passively. Living mulch cooled actively through transpiration, creating a micro-climate.

Surface Temperature Comparison Chart

The chart above visualizes surface soil temperature differences observed during the trial. Live ground cover dramatically suppressed heat compared to bare soil and dead mulch.

Strategy One: The Green Carpet (Living Mulch)

We no longer weed aisles. We manage them. Low-growing, spreading crops are deliberately grown beneath main crops to form a living insulation layer.

Sweet potato proved the most effective in Birbhum. It spreads rapidly, roots at nodes, and produces food. Pumpkin provides heavy shading but demands more water. Fodder cowpea shades soil while fixing nitrogen.

Management is critical. Living mulch must be chopped and dropped if it competes upward. It is a servant, not a master.

Strategy Two: Vertical Mulching (The Water Battery)

Laterite sheds water sideways. Vertical mulching forces it down.

We dig banana circle pits or auger holes one foot deep every ten feet and fill them with woody debris such as sticks and coconut husk. Irrigation and rainwater are directed into these pits.

The woody material functions as a carbon sponge. It absorbs water and releases it slowly through fungal networks, maintaining subsoil moisture even when the surface is dry.

Failure Logs From the Field

In 2023, loose paddy straw used during Kalbaishakhi storms blew away, removing over half the mulch. We corrected this by lightly binding straw with cow dung slurry or switching to heavier biomass.

In another case, ten-inch mulch piled against tree trunks created rodent nesting zones. Rats girdled fifteen lemon trees. We now maintain a strict six-inch bare soil ring around trunks. Mulch begins beyond that zone.

Failure teaches faster than success.

Cost Versus Benefit Reality

| Method | Monthly Cost Per Acre |

|---|---|

| Daily Watering (depends on crops) | ₹7,500 |

| Live Mulch + Weekly Watering | ₹2,000 |

| Monthly Savings | ₹5,500 |

These savings arise from reduced pumping, lower labour, and stabilized plant survival.

The Soil as the Cistern

One percent soil organic carbon holds roughly 16,000 litres of water per acre in the top six inches. At two percent, that doubles. Ponds and pumps matter, but the largest water tank on the farm is the soil itself.

You do not need a bigger pump.

You need a bigger sponge.

Final Position of Terragaon Farms

Lateritic soil cannot be kept alive by watering alone. It must be insulated, biologically connected, and structurally charged.

Watering feeds plants.

Insulation feeds soil.

Only one sustains life in Birbhum summers.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why does surface watering fail in laterite soil

Because evaporation exceeds infiltration at high temperatures, causing crusting and moisture loss.

Is straw mulch enough to protect soil

It cools passively but does not create micro-climates like living cover does.

What is the best living mulch for Birbhum

Sweet potato performed best due to rapid spread and active transpiration.

How does vertical mulching help

It stores water underground in carbon-rich material and releases it slowly.

Can this reduce irrigation costs

Yes. Field data shows savings of over ₹5,000 per acre per month.

Next Step

Field Action: Go to your field at 2 PM. Place your hand on the soil. If it is too hot to keep your palm there for 10 seconds, your soil microbiome is dying.

Krittika Das is a field practitioner and primary author at Terragaon Farms in Birbhum, West Bengal. Her writing is grounded in daily farm work, long-term soil observation, and small-land realities of eastern India. She focuses on natural farming, soil ecology, ethical dairy, and low-input systems, translating field experience into clear, practical knowledge for farmers and conscious food consumers.